A Review of Into the Woods

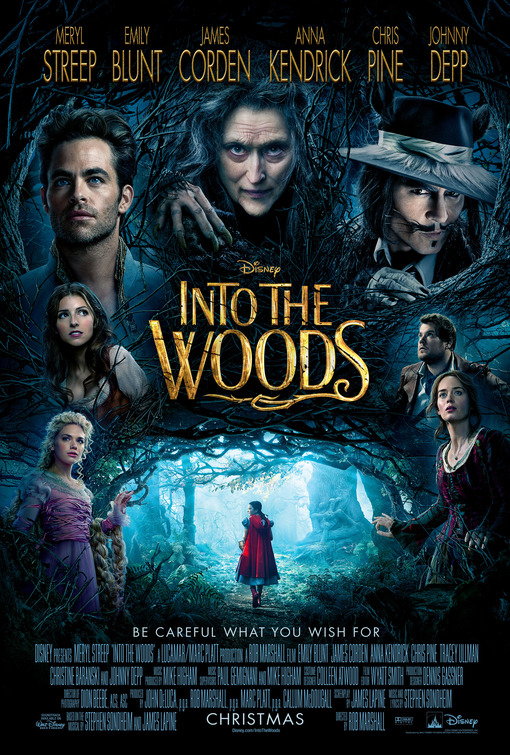

Admittedly, I know nothing of the musical Into the Woods besides a heavily edited high school performance seen well over a decade ago. It didn't make an impression then either. The premise of the story, an intertwining of plots and characters from several fairy tales (Grimm originals, to boot), seemed promising. That and the the all-star cast line-up enticed me to click play while I was browsing Netflix one evening.

|

| source |

The beginning is the best part of the whole film. It only goes downhill from there. The way the stories wove together were, well...passable. And that's the best I can say about it.

I liked the setup, placing the baker and his wife into the Rapunzel tale. The expectation of things coming together, especially the opening song, had my attention. Emily Blunt performs very well as the Baker's Wife, combining musical dialogue with humor. I'm fond of James Corden and pleased with his casting. Little Red Riding Hood's introduction as the glutton is cute as well. Interesting parallels there between her and the wolf.

As the movie played on, I felt a gaping lack of attachment to the characters--other than Mr. and Mrs. Baker: infertility is a profound struggle that touches far too many. And Emily Blunt carried that for me. The princes bored me to tears. Rapunzel was a nobody; Cinderella was, as the witch says, merely "nice;" and the children are downright annoying. Is the head-slapping relationship between Jack and his mother supposed to be endearing?

|

| source |

Meryl Streep's character is meant to express moral ambiguity, I get it, but there should have been some sort of tie-in between the bakers' infertility and her kidnapping the baker's sister to be her adoptive daughter. What we get is tiresome sung-exposition. Insert the Willy Wonka Gene Wilder meme here: Tell me again about the complex parent-child relationship that plays out in complex ways and is complex!!!! The witch having never previously expressed a desire for a child and the total lack of screen time between her and her "daughter" killed the effectiveness of any would-be emotional impact. We could have done with a little character development.

|

| source |

In the end, the characters all work together and all get their wishes.

But--this musical wants to slap it into our heads as surely as Jack's mother--you should be careful what you wish for. After the curtains close on the traditional endings, there is still another dragging hour of movie left; during which, in-between trying to avoid the wrath of a giantess, they all come together to be communally unsatisfied. A theme that feels heavy-handed and forced, desperate to join the lineup of postmodernist deconstructed fairy tales. The deaths are stupid and pointless. The ending utterly anti-climactic. Into the Woods tries be profound and it's just not. Somehow, that is worse than if they'd decided to say "sod it all!" and just make something fun and ridiculous.

Wikipedia reports that the play's

basic insight ... is at heart, most fairy tales are about the loving yet embattled relationship between parents and children. Almost everything that goes wrong — which is to say, almost everything that can — arises from a failure of parental or filial duty, despite the best intentions.

Nothing that the original stories didn't already do, and do better.

What did you think of this film? How does it compare to the musical? Did I miss something essential that would have otherwise earmarked this a landmark production?