A Review of Disney's Maleficent

The first thing I do after watching a movie is to head over to Rotten Tomatoes to peruse the film reviews by proper critics. The second thing I do, if it is a fairy tale movie, is to hit up all my fairy tale blog peeps for a more balanced perspective. Sadly, my colleagues have been rather silent on the matter, with a few exceptions, so I suppose I ought to help get the ball rolling.

|

| source |

We've been hearing about Maleficent for years, but in the end my experience of the film can be summed up in one word: bored. I don't know if I'm the best judge of entertainment, since I have a peculiar and finicky taste, but from the opening voice-over to the ending credits, I found little to hold my attention. If it had not been for the pretty costuming and talented actresses, I might have lost interest entirely. It was just all very tepid, underneath the fancy CG. I didn't feel there was much at stake. Maleficent lost her wings, and her love, but she was good and happy before she met Stefan and during his absence. If she could walk into the castle to curse a baby, surely she could have retrieved her wings while she was at it. Even the curse is tamed to a sleep-like death, without a desperate, last minute intervention from a good fairy.

|

| "Mom, is that you?", source |

The supporting characters are boiled down to their lowest common denominators, becoming tedious distractions rather than tools to help the story along. Certainly not characters in their own rights, with complexities and inner goings-on.

Stefan is a kind of caricature born out of the necessity for a villain, and his motivation is weak. The filmmakers need to give us a little bit more to work with if they want us to meet them in the middle; it's hard enough to believe that a kind boy, who would throw away his iron ring because it hurt a magical creature he only just met, would then become so heartlessly ambitious so as to turn around and try to kill the same creature, someone he cared for enough to have spent time growing up with her.

The pet raven is given a speaking voice by occasionally taking the form of a human but still doesn't have much to say.

In the end, Maleficent and Aurora alone are given room for growth and exploration, while the other characters and plot developments move around like props. But even poor Aurora's character is charming and bland. Her greatest moment is when she speaks out to the witch hiding in the shadows and does not recoil from her. Not much of a monumental and memorable game-changer.

For me, the most engaging moment of the whole movie was when Maleficent stands over the sleeping Aurora and wills her curse undone, only to have it thrown back in her face. And I credit all that to Ms. Jolie's powerful acting. (Also done well in the moment she realizes her wings have been taken from her. Maybe a tad melodramatic, but so wrenching and real that it made me hurt for her!)

Adam of Fairy Tale Fandom writes,

[Maleficent is] about two people and how their hearts become darkened by ambition, anger, bitterness and revenge. It’s also about how one of them starts to regain some light through exposure to someone who is good and innocent.

and I think he's absolutely right. But I feel like the key relationship, between Maleficent and Aurora, is not given any time to develop, what between Maleficent watching her in her sleep and Aurora playing in the Moors with the magical creatures which are all show and no soul--the eeriness of Faerie is lost in this film, and I'd like to think I've cultivated a good radar for it. In Brave, for instance, that otherworldliness remains intact. It's hard for me to suspend disbelief and get behind Aurora's running away to the magical Moors forever, when it's just. So. Boring.

|

| laughing and twirling and playing with magical creatures can only entertain me for so long source |

Besides that, there were a lot of other little frustrations. How did the writers choose which elements of their original movie to keep? When does one draw the line?

"We won't have Maleficent turn into a dragon, but we still need a dragon, so we'll have someone else be it."

Or, "there's no need for thorns around the castle, but it's such a major element to the original, so we'll have thorns protecting Faerie instead."

Even the spinning wheel is chosen because Maleficent happens to see it when placing the curse. I much prefer the mystery of not knowing to that. Why would a benign fairy even be named Maleficent, for that matter? I hoped it would be a name she took on, as she did her new staff and cloak. But apparently her parents had a strange sense of humor, or else didn't have a dictionary on hand at her christening.

|

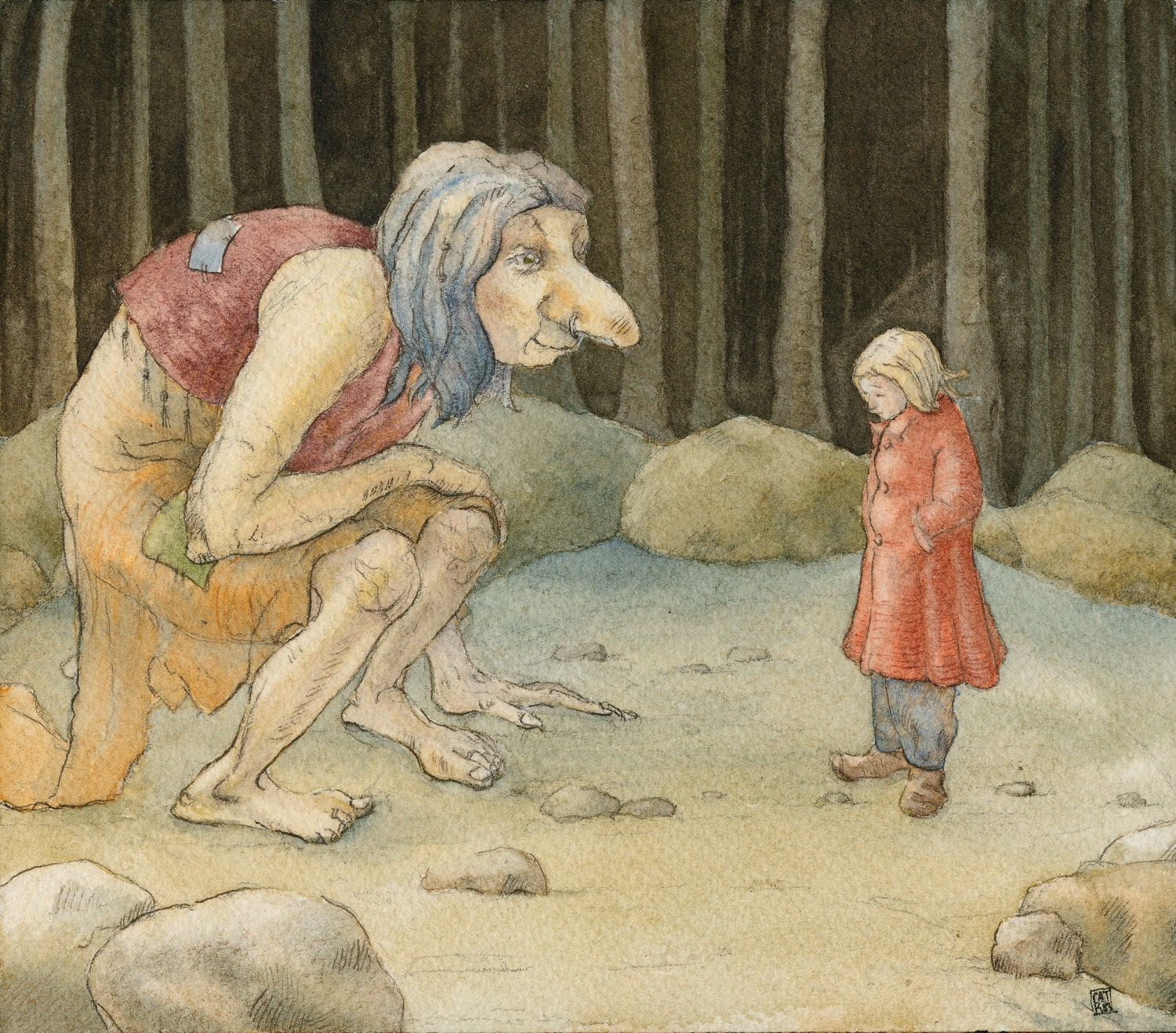

| irrelevent but still interesting, source |

When I was a little girl, I lived and breathed Sleeping Beauty. It was my absolute favorite Disney movie. I wanted to be Aurora/Briar Rose. And I never wanted or needed an explanation for the, well, maleficence of Maleficent.

While I'm all for revisionist re-imaginings and villainous back stories, I worry this new trend is overlooking an important aspect of fairy tales: the fact that there is evil and ugliness in the world, just as there is hope and unspeakable beauty. To try to reason away these things (or, as the case may be, relegate them to a bland, mortal antagonist) steals a little bit of their wonder, and it robs us of one of the great consolations of fairy tales. Whatever the reasons may be for them, dragons exist, and so do wicked fairies. Yet there is always hope: a low door in the wall, a maiden's tears; a magic circle, a fairy godmother; a hole in the spell, one last gift-bearer overlooked and forgotten. The bad is not absolute, though it may seem impenetrable as a wall of thorns.

And even death becomes only sleep in the end.

Death be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for, thou art not so,

For, those, whom thou think'st, thou dost overthrow,

Die not, poore death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

From rest and sleepe, which but thy pictures bee,

Much pleasure, then from thee, much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee doe goe,

Rest of their bones, and souls deliverie.

Thou art slave to Fate, Chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poyson, warre, and sicknesse dwell,

And poppie, or charmes can make us sleepe as well,

And better then thy stroake; why swell'st thou then;

One short sleepe past, wee wake eternally,

And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.